Written by admin

Posted on: June 21, 2020

“Of all the forms of inequality injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhumane.” – Martin Luther King, 1966.

In the turmoil that is gripping our nation right now a potential for healing and real change is emerging. Many white hearts are opening and really listening to black voices. I think many are untangling the ways white privilege spread roots within us without our conscious knowing or consent. We are reaching in and trying to pull those weeds. My own journey in this regard began several years ago after some powerful sermons from my pastor directly confronting white privilege. Recent events have heightened this and brought an urgency to listen to voices in pain, do this work, and guide our children to a better future.

I have been thinking a lot about racial disparities in medicine and reading Black Man in a White Coat by Damon Tweedy. Tweedy notes that the problems leading to health disparities negatively impacting black people take three forms.

- System-based disparities limiting black people’s access to care.

- The doctor-patient relationship itself, the attitudes and behaviors of both doctors and patients.

- Unhealthy lifestyle behaviors.

Of course, we need to continue to focus on the global, system-based disparities and access to care through advocacy, legislation, and any other means. But right now, more than ever, feels like the time to focus on Tweedy’s second point through one-on-one human connection.

Tweedy writes, “Some doctors are prone to hold negative views about the ability of black patients to manage their health, and therefore might recommend different, and potentially substandard, treatments to them.”

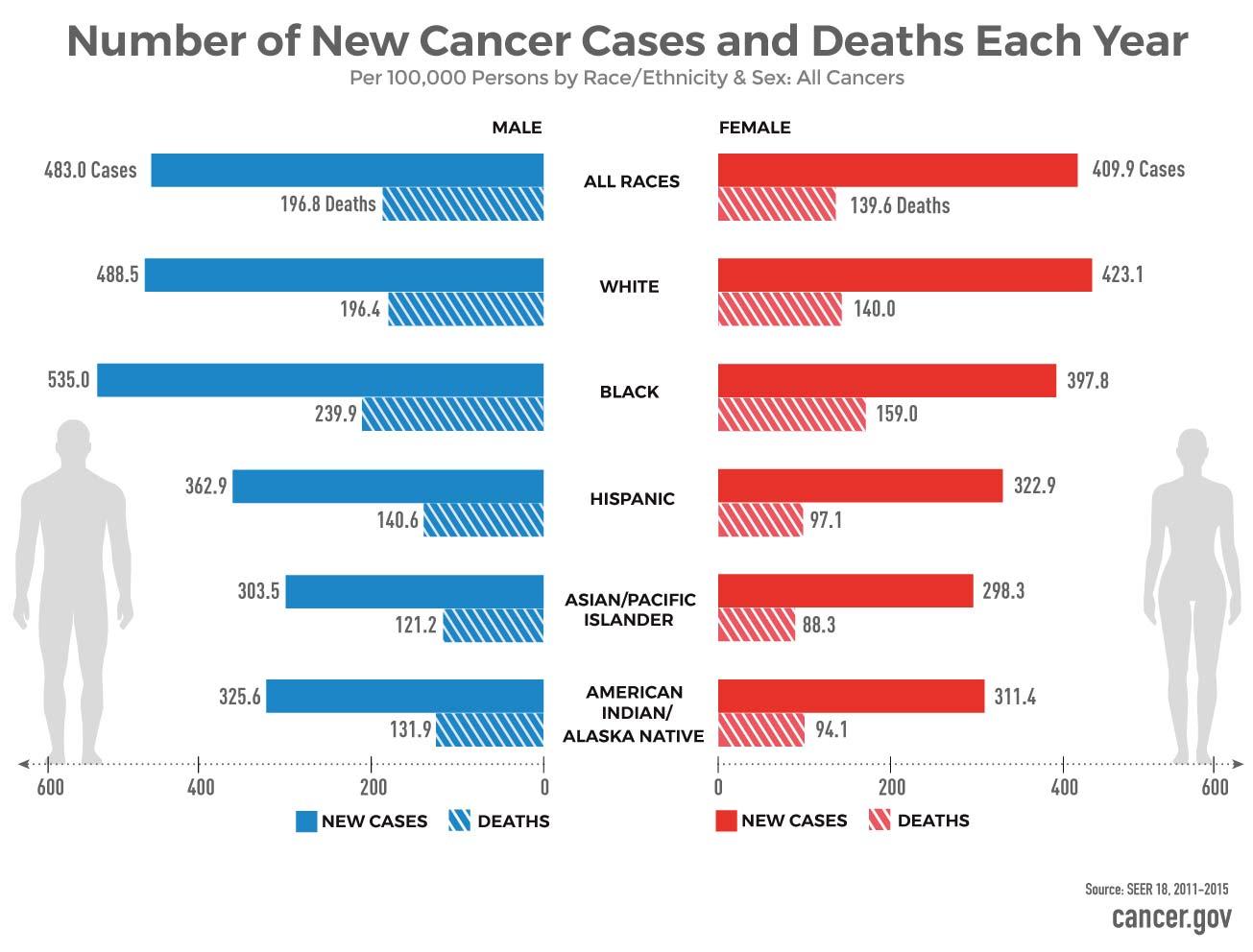

Here are a few facts regarding racial / ethnic disparity in cancer care from the NIH website.

- Breast Cancer: African American women are much more likely than white women to die of breast cancer.

- Prostate and Stomach Cancer: African American men are roughly twice as likely as whites to die of prostate cancer and stomach cancer.

- Colorectal Cancer incidence is higher in blacks than whites

- Cervical Cancer: Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska Native women have higher rates of cervical cancer and African American women have the highest rates of death from the disease.

- Biliary Cancer and Kidney Cancer: American Indians/Alaska Natives have the highest rates of liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer and higher rates of kidney cancer.

- Lung Cancer: Both the incidence of lung cancer and death rates are higher in African American men than in men of other racial/ethnic groups.

Some of these disparities have biological mechanisms. For example, black women are nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, which is more aggressive and harder to treat. Prostate cancer in blacks also tends to be diagnosed at a younger age and be more aggressive. Indeed, starting earlier prostate cancer screening for black men is recommended.

Educational differences have been noted including the fact that people with more education are less likely to die prematurely of colorectal cancer than those with less education, regardless of race or ethnicity. This is reflected in the increased rates of colorectal cancer deaths among those younger than 65 are in states with the lowest education levels.

Reflecting Tweedy’s third point, the NIH points out differing rates of cancer incidence and deaths could also be a manifestation of different rates of behavioral risk factors in poor and medically underserved individuals, such as smoking, physical inactivity, obesity, increased alcohol intake, all factors tied to increased cancer risk.

However, many of the cancer disparities are driven by socioeconomic inequalities and societal institutionalized racism. Access to health care is one of the biggest. We must find ways to identify and then close these barriers. Delaware’s program to address colorectal screening disparities among African Americans is an example of success. The state created a screening program, paid for screening and treatment, and made patient navigators available to help patients coordinate their care. By 2009 Delaware had eliminated disparities in screening rates, led to cancer diagnosed at earlier stages, and almost eliminated the racial differences in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Recognition of racial disparities in cancer care is the first step. In my opinion the next place to start is in the human connections we experience each day. Tweedy writes,

“A big part of the solution is discarding your assumptions and connecting with each patient as a person… It is up to us, as doctors, to find the commonalities and respect the differences between us and our patients. In that way, we can understand what they value, how best to communicate with them, and how to arrive at treatment plans that improve their health while respecting their wishes. This approach is often called cultural competence, but after years of medical practice, it seems to me more like common sense.”